I was headed to tell my dad I had wrecked the car.

Driving with my buddy in Greenville, S.C., we came off an exit ramp—perhaps a bit too fast, but nothing reckless—fast enough, however, to cause the car to skid off the road and hit some cement below and mess up the axle. It was going to be several hundred dollars worth of damage.

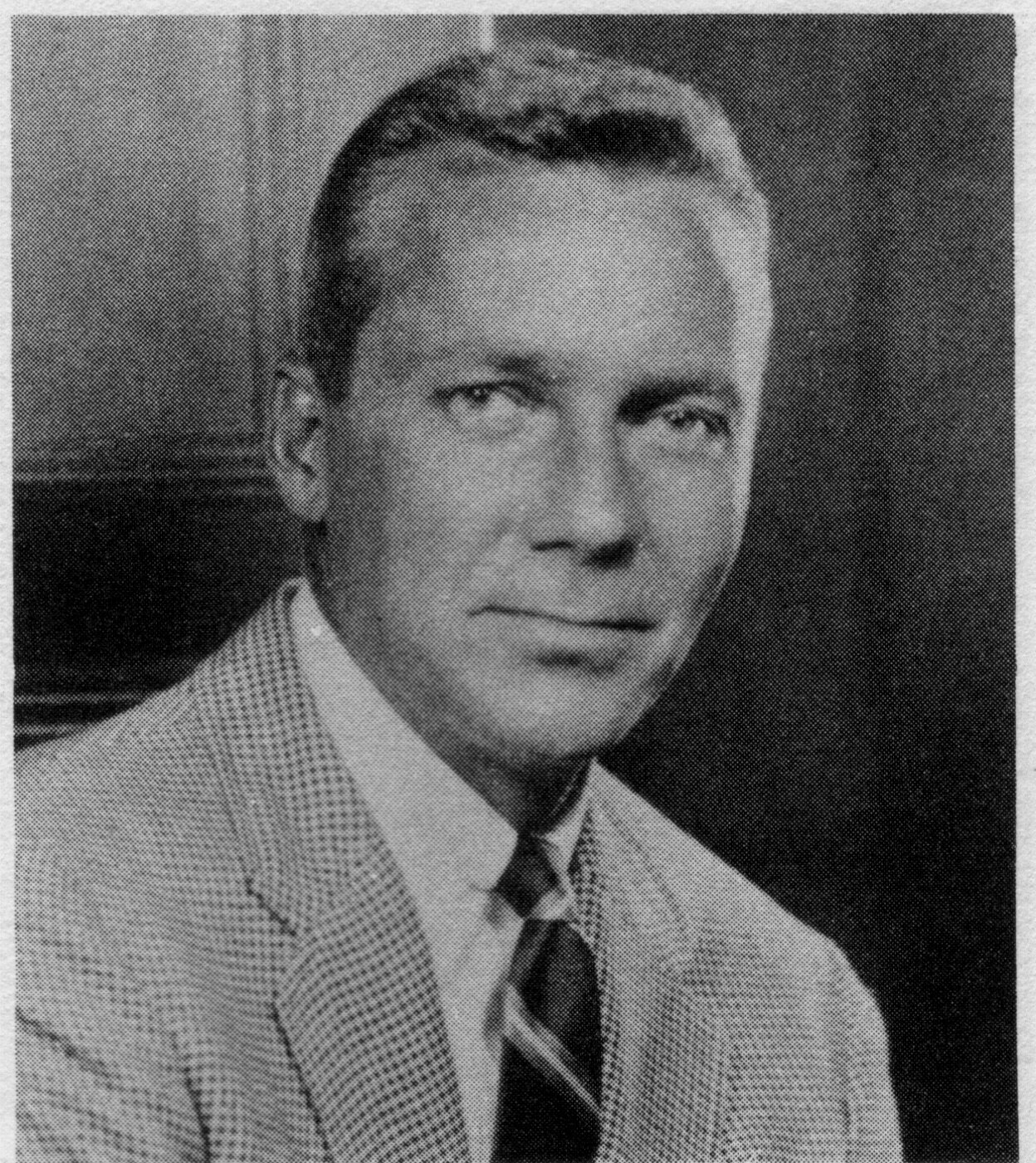

Dad was six-foot-four, looming, a former basketball player at a major college. I’m not quite six feet. Dad was an authoritarian, an alpha male, large and in charge, with an unpredictable temper.

My Father, Jack Arnold

I told him what happened to the car, and, as I’d feared, he lit into me with a rage, dressing me up and down and treating me like I was 10 years old.

But I was 20. For the first time in my life, I got back in his face and told him to back off. “I don’t deserve to be treated that way,” I said. “Your anger is inappropriate. So I wrecked the car? I’ll pay for it. Whatever. But this is not how I should be treated.”

The story ends well. He looked at me, grumbled, turned and walked away. And that was the extent of it. I don’t think I even had to pay for the damages.

“All men are in some way at war with their fathers,” said Rick Montague, when I interviewed him for my book, Old Money, New South: The Spirit of Chattanooga. Rick made this profound statement while describing the relationship between Jack Lupton and his father, Cartter Lupton, heirs of the great Coca-Cola bottling fortune. (Rick, the father of Jack’s grandson, ran the younger Lupton’s Lyndhurst Foundation in the 1980s.)

Jack Lupton

Cartter Lupton was known as “Mr. Anonymous.” He was the quintessential institutional man during an institutional era, and he was a solid, faithful member of the First Presbyterian Church. Jack was a maverick who hated institutions. He was the first Lupton in several generations to leave the Presbyterian church. Jack was very public about some of his gifts, such as the Aquarium, in order to strategically leverage more gifts from other prominent citizens. Cartter generously supported the systems of the 1950s and 60s. Jack worked to change those systems and overhaul the city.

“They all buttoned it up at night and went home to their little bitty conclaves,” Jack said about his father and his colleagues. “They didn’t want anybody knowing about what a nice little deal they had here.”

Other notable families in Chattanooga had similar disagreements with their fathers. Former SunTrust Chairman Scotty Probasco, Jr., told his father the city needed to grow, but his dad, also the town’s major banker, discouraged the talk. “They didn’t really want growth because it competed for labor,” Scotty confided. “He was a hell of a man. A natural leader,” Scotty said, “(but) people were all scared of my dad.”

Frank Brock tells a similar story regarding conversations with his father and brother, all executives and owners for the South’s largest candy manufacturing business. “I do remember my father saying, ‘I don’t know why everyone wants to grow so much,’” said Frank. “And my brother and I used to say . . . ‘You’ve got to grow.’ And he said, ‘Well, you don’t have to grow fast.’”

Frank Brock

“One of the values, if you will, that Chattanooga had,” said Frank, “is that we didn’t want to grow up.”

I think Frank’s observation is true for individuals as well. At some point, a son must grow up in his own eyes and in the eyes of his father. I’m told that every young man must stand up to his father at some point in his life in order to advance to true adulthood.

It wasn’t until my own father’s funeral that I realized how important that confrontation in Greenville over the car had been to my formation as a man. I am the youngest of four boys. All of us spoke at Dad’s funeral, and it became clear to me that day that two of us were at peace with our father, and two of my brothers had not yet resolved their relationship with him.

Dad and his sons

As I searched my mind and heart, I realized that when I confronted him that day in Greenville, I learned many things. I learned that courage pays off. I learned that although my Dad had a temper, he was a fair man. I learned that if I confronted him, he would treat me like an equal and the outcome would be based on the merits, not on his authority. I learned confrontation is not disrespectful and that to “honor your father” is not the same as to cower to your father. Most significantly, I learned that I had grown up.

I don’t think there is much doubt that Jack Lupton found an opportunity to confront his father. “They wanted to keep this place a secret,” Jack said. “Well, they were full of s***, as far as I am concerned. And I told him so, in just those words, a good while ago.”

I encourage parents, especially mothers, not to get too alarmed when your son has such a confrontation with his dad. It may simply be a rite of passage that makes everyone better. And I hope that I have a good perspective when my own son, not yet a teenager, suddenly responds to my directives as a 20-something with his own sense of authority.

I think all this may work differently with women. My 14-year-old daughter has no trouble confronting me, early and often.

Originally published in 2009.